When a Child Does Fine on Homework but Fails Tests

- Susan Ardila

- Jan 9

- 11 min read

Homework is perfect.

Practice problems go smoothly.

Confidence seems steady.

Nothing feels off.

And then the test happens.

Suddenly, the child who just worked through twenty nearly identical problems without hesitation is stuck. They freeze. They guess. They stare at the page like it’s written in another language.

Parents almost always ask the same question:

“How did they get all the practice problems right… and then fail this?”

It feels illogical. Random. Infuriating.

It also feels personal—like effort must have dropped, focus must have slipped, or motivation must be the missing piece.

Here’s the part most parents aren’t told:

This pattern is not a contradiction. It’s a signal.

In my work outlining the Nine Hidden Faces of Dyscalculia™, this is one of the most commonly misunderstood profiles I see—precisely because everything looks “fine” right up until it suddenly isn’t.

And when we treat this pattern as inconsistency instead of information, we miss what the math is actually telling us.

Why Doing Fine on Homework but Failing Tests Is a Red Flag

When a child does fine on homework but fails tests, it’s tempting to chalk it up to nerves, pressure, or a bad day.

But this pattern isn’t random—and it’s not about effort.

Homework success is often misleading because homework is designed to be predictable.

The format is familiar.

The structure doesn’t change.

The steps are rehearsed repeatedly.

By the time a child reaches the last few problems on a homework set, they already know what the concept is and what kind of answer is expected. The task becomes execution, not thinking.

Tests, on the other hand, quietly change the rules.

The concept might be the same—but the presentation isn’t.

The numbers might look different.

The problem might be embedded in a word problem.

The student might have to work backwards, choose a strategy, or decide which procedure even applies.

That’s when everything falls apart.

Not because the child forgot.

Not because they weren’t trying.

Not because they suddenly stopped caring.

But because the math stopped looking exactly like the example.

When a child does fine on homework but fails tests, what you’re often seeing is the predictable exposure of a learning imbalance—one where procedural execution has been practiced extensively, but conceptual understanding and transfer were never required.

This is the moment parents usually start blaming effort.

It’s also the moment they should stop.

Because what looks like inconsistency is actually very consistent.

And once you know what to look for, it becomes impossible to unsee.

Introducing the Procedural Performer

This is the point where most parents finally get language for what they’ve been seeing—but couldn’t explain.

The Procedural Performer is not a student who is “bad at math.”

They’re also not simply “good at math.”

They are something much more specific—and much more overlooked.

A Procedural Performer is a student who shows:

Strong procedural execution

Weak conceptual grounding

Poor transfer when the structure changes

They can follow steps accurately.

They can replicate examples flawlessly.

They can complete assignments that look exactly like what they’ve practiced.

But the moment the math asks for flexibility—when the format shifts, the question is embedded in a word problem, or the steps aren’t obvious—their performance collapses.

This is why the usual labels fail so badly.

“Good at math” and “bad at math” don’t tell us how a child is succeeding or struggling. They flatten everything into outcomes and completely miss the process underneath.

Procedural Performers aren’t failing math.

They’re succeeding in a very narrow way.

Or, put more bluntly:

They’re not bad at math. They’re very good at following instructions.

That distinction matters—because following instructions is not the same thing as understanding what you’re doing.

And when instruction is removed, variation is introduced, or reasoning is required, the cracks finally show.

When Accuracy and Speed Become a Risk Factor

This is where things get uncomfortable—especially for well-meaning parents and teachers.

In school, accuracy and speed are treated as unambiguous positives.

Finish quickly.

Get the right answer.

Move on.

And for Procedural Performers, this system works beautifully—right up until it doesn’t.

Here’s how the feedback loop forms:

Speed is praised.

Accuracy is rewarded.

Explanations are optional.

No one asks why the steps work.

No one checks whether the student can apply the idea in a new way.

No one notices that understanding was never required.

Over time, the child learns exactly what earns approval.

Not sense-making.

Not reasoning.

Not flexibility.

Execution.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth most systems miss:

This isn’t neutral encouragement. It actively reinforces procedural dependence.

When a child does fine on homework but fails tests, it’s often because homework has rewarded accuracy without ever testing understanding. The very thing that makes them look successful is what keeps the learning difference hidden.

This is why strong performance can actually delay identification of a real learning difference.

The system reads “correct” as “competent.”

The child reads “praised” as “safe.”

And no one realizes how fragile that success is until math finally demands more.

The Moment Everything Falls Apart

If you’ve seen this profile in action, you know the moment exactly.

Practice problems go perfectly.

Same concept.

Same steps.

No hesitation.

Then come the last few questions.

They’re word problems—but still on the same exact concept.

And suddenly, the student can’t even start.

Not a wrong answer.

Not a small mistake.

Nothing.

They stare at the page.

They reread the problem.

They look stuck in a way that feels out of proportion to the task.

This isn’t forgetting.

It isn’t anxiety—at least not at first.

It’s something more precise:

There’s no procedure to grab onto.

The structure changed just enough that the memorized steps no longer apply cleanly. And without meaning to guide them, the student has nowhere to go.

What shows up emotionally isn’t confusion—it’s frustration.

Frustration rooted in self-blame.

“I should know this.”

“I was just doing this.”

“What’s wrong with me?”

Parents recognize this instantly, even if they can’t name it yet. The child isn’t disengaged. They’re upset with themselves for not understanding why what worked a moment ago suddenly doesn’t.

That emotional response is one of the clearest tells of the Procedural Performer profile.

Why Word Problems Act Like a Stress Test

Word problems don’t cause this struggle.

They reveal it.

Think of word problems as a kind of stress test for mathematical understanding.

They strip away procedural cues.

They remove the obvious steps.

They require the student to understand the situation before choosing a method.

In other words, they demand meaning before mechanics.

This is where an imbalance becomes visible—one that often goes unnoticed for years.

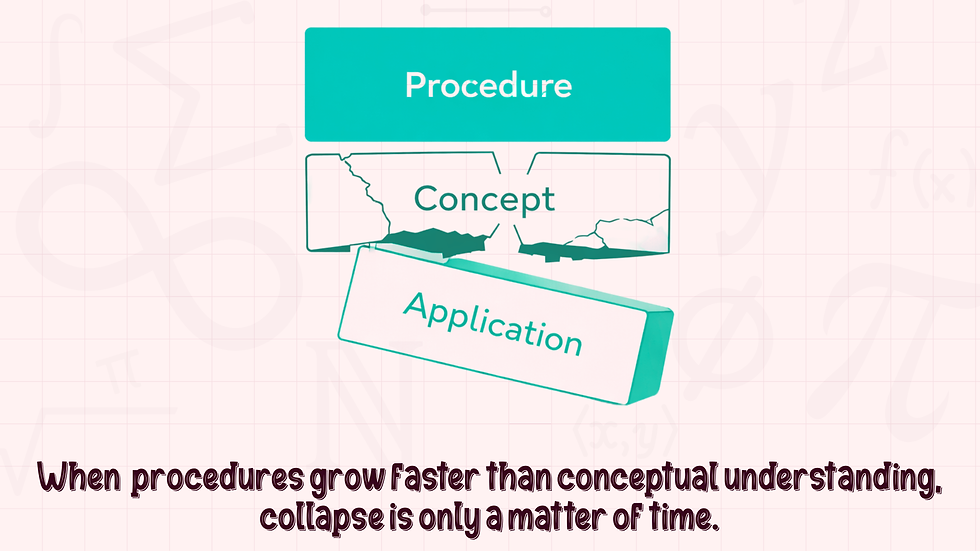

Mathematical proficiency isn’t a single skill. It’s a balance of three strands:

Procedural – knowing how to carry out steps

Conceptual – understanding why those steps work

Application – knowing when and where to use them

Procedural Performers are often overloaded on the first strand and underdeveloped in the other two.

As long as tasks stay procedural, they thrive.

The moment application or conceptual reasoning is required, performance drops.

That’s why word problems feel so destabilizing. They expose the gap between execution and understanding.

And once you see word problems this way—not as “harder math,” but as a diagnostic lens—the pattern stops looking mysterious.

It starts looking inevitable.

This is also why I built the MindBridge Resource Vault.

Many parents don’t need more worksheets — they need ways to see whether understanding is actually there. The Vault includes tools designed to surface conceptual thinking, encourage explanation, and test transfer without pressure or speed — especially for students who look successful until the format changes.

“It Looks Like Anxiety, But It Isn’t”

This is usually the point where parents are told, gently but incorrectly, that their child is just an anxious test-taker.

“They freeze under pressure.”

“They panic during tests.”

“They know the material, but anxiety gets in the way.”

On the surface, that explanation feels reasonable. The child does freeze. The frustration does show up most clearly during tests or word problems.

But here’s the problem with that narrative:

It blames the child for reacting to an environment that was never designed to support how they learned.

What looks like anxiety is often something much more specific—and much more fixable.

Procedural Performers don’t freeze because they’re nervous.

They freeze because the math suddenly asks for flexibility they were never taught to build.

When instruction emphasizes execution over meaning, students learn to rely on steps as their safety net. As long as the structure stays familiar, they feel steady. The moment it doesn’t, that safety net disappears.

Of course they freeze.

That freeze isn’t a character flaw.

It’s not a confidence issue.

And it’s not a lack of resilience.

It’s the natural response of a student who has been trained to follow instructions—but not to reason independently when those instructions change.

Here’s the line parents often need to hear the most:

You can’t be confident about math you don’t fully understand.

Confidence doesn’t come from getting answers right over and over. It comes from knowing why something works—and being able to adapt when it doesn’t look exactly the same.

Until that understanding is built, labeling the response as “anxiety” only obscures the real issue.

Procedural Performer vs. Conceptual Stranger

This is where clarity matters.

Because on the surface, Procedural Performers and Conceptual Strangers can look similar. Both may pass classes. Both may surprise adults with sudden breakdowns. Both often go unnoticed longer than they should.

But the cause of the struggle is fundamentally different.

Conceptual Stranger: meaning was never formed

Procedural Performer: meaning was never required

That distinction is everything.

The Conceptual Stranger is navigating math without understanding from the start.

The Procedural Performer is navigating math successfully—as long as understanding isn’t demanded.

Here’s the clean boundary I use clinically, and it matters:

If your child executes algorithms with ease but falters when faced with a novel context or non-routine problem, you’re likely looking at a Procedural Performer—not a Conceptual Stranger.

This isn’t about intelligence.

It isn’t about effort.

And it certainly isn’t about “not trying hard enough.”

It’s about what the learning environment asked for—and what it didn’t.

Keeping this distinction clear protects parents from chasing the wrong explanations and applying the wrong supports. And it keeps the framework honest.

What Parents Should Stop Doing Immediately

When a child does fine on homework but fails tests, the instinctive response is almost always the same:

More practice.

More worksheets.

More step-by-step repetition.

More of the exact thing that already “worked.”

And I understand why. Repetition feels responsible. It feels supportive. It feels like you’re doing something.

But for Procedural Performers, this is where well-intentioned help quietly backfires.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Repetition strengthens the pathway the child is already relying on.

If that pathway is execution without meaning, drilling more problems doesn’t build understanding. It deepens procedural dependence.

So this is the moment to pause—and gently but firmly change course.

Stop drilling more worksheets hoping repetition will finally “make it click.”

Stop equating accurate answers with mastery.

Stop assuming that speed is a sign of confidence or competence.

Accuracy tells you a child can follow steps.

It does not tell you they understand what those steps mean.

And when understanding hasn’t been built, no amount of extra practice will suddenly create it. It will only make the collapse more confusing later.

This isn’t about doing less.

It’s about doing different.

What Actually Helps (and Why It Feels So Different)

What helps Procedural Performers doesn’t look impressive on paper—and that’s part of why it’s so often skipped.

Real understanding is built through:

Variation instead of sameness

Explanation instead of execution

Prediction before solving, not after

Working backwards, not always forward

These moves force the brain to engage with meaning before mechanics.

They remove the safety net of memorized steps.

They surface gaps without shaming.

They make thinking visible.

This is also why effective support for Procedural Performers often feels uncomfortable at first—for the student and the adult.

Because this is not how most classrooms are set up.

And it’s not how most tutoring is structured.

Most systems reward correct answers.

This approach asks whether those answers actually make sense.

That difference matters more than any worksheet ever will.

Why This Matters More Than Grades

Grades are excellent at measuring performance.

They are terrible at predicting sustainability.

A child can earn strong grades for years while quietly relying on fragile strategies that only work under perfect conditions. When math becomes more abstract, more flexible, or more conceptual—as it inevitably does—that success can unravel fast.

This is why the opening contradiction matters so much:

Homework looks perfect.

Practice goes smoothly.

Then the test happens… and everything collapses.

That pattern is not a mystery.

And it’s not a personal failure.

The Procedural Performer profile is common.

It is addressable.But only when it’s correctly identified.

Once parents stop chasing effort and start understanding how their child is learning, the path forward becomes much clearer—and far less frustrating.

A Clear, Grounded Next Step

If this post described your child with uncomfortable accuracy, the next step isn’t more practice.

It’s clarity.

I offer free parent consultations designed to help families:

identify which learning profile they’re actually seeing,

understand why certain supports haven’t worked, and

map out next steps that build real understanding—not just better performance.

`

There’s no pressure and no sales pitch. Just a clear conversation about what’s really going on and what will actually help.

This profile is just one part of a larger framework I outline in The Nine Hidden Faces of Dyscalculia™, where I explain why math struggles don’t come from a single problem—but from distinct, often invisible learning patterns that schools aren’t trained to recognize.

If you haven’t read the pillar post yet, it’s worth starting there. And if you have, this piece will likely make a lot more sense now.

Because procedural success can look like mastery—until math asks for understanding.

About the Author

Susan Ardila, M.Ed. is an educational clinician, dyscalculia specialist, and multisensory math educator with over a decade of experience working with neurodiverse learners. She specializes in identifying hidden math learning profiles—especially students who appear successful on paper but struggle when math demands real understanding, flexibility, or transfer.

Through her work at MindBridge Math Mastery, Susan helps families move beyond grades, speed, and rote performance to uncover how a child is actually learning—and what that means for long-term success. Her approach blends cognitive science, clinical observation, and deeply practical insight, giving parents language for struggles schools often overlook.

Susan is known for naming what others miss, challenging oversimplified “good at math / bad at math” narratives, and helping families replace confusion with clarity. Her writing reflects what she sees every day in practice: that math struggles are rarely about effort—and almost always about how understanding is (or isn’t) built.

References & Further Reading

Conceptual Understanding vs. Procedural Fluency

Adding It Up – National Research Council

A foundational text on mathematical proficiency and the balance between conceptual understanding, procedural fluency, and application.

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Principles to Actions: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All

Explores why procedural success alone is insufficient for sustainable math learning.

Conceptual and Procedural Knowledge in Mathematics – Hiebert & Lefevre

A seminal analysis distinguishing between knowing how to do math and understanding why it works.

Transfer, Flexibility, and Deep Learning

How People Learn – Bransford, Brown, & Cocking

Examines how learning transfers—or fails to—when understanding is shallow or context-bound.

Why Don’t Students Like School? – Daniel T. Willingham

Explains why students struggle with transfer and why practice alone doesn’t create understanding.

Make It Stick – Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel

Discusses why repetition without variation reinforces fragile learning.

Dyscalculia and Hidden Math Learning Profiles

Dyscalculia – Brian Butterworth

A comprehensive look at the cognitive foundations of mathematical learning difficulties.

Mathematical Disabilities – David C. Geary

Explores how different cognitive profiles affect math learning beyond surface performance.

Kaufmann, L., et al. Dyscalculia and Learning Difficulties in Mathematics

Research on how math difficulties can remain hidden behind procedural competence.

Assessment, Performance, and the Illusion of Mastery

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. Desirable Difficulties in Theory and Practice

Explains why ease and fluency during practice can be misleading indicators of learning.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence

Highlights why instructional design—not learner effort—is often the real variable.

The insights in this post are grounded in both research and years of clinical practice, where patterns become impossible to ignore once you know what to look for.

Comments